Introduction

Whilst Utilization is important, it is only one facet of the supply and demand for space. From a real estate perspective, Utilization is good at establishing what and how much is being used. This is important in understanding the relative costs of providing the space that is being used, or indeed the cost of the space that isn’t being used.

However, when considering Space from the point of view of the people who are using it, Utilization is of limited interest. People are not normally overly aware or indeed concerned about levels of Utilization, until and unless the use of the Space begins to impact them or their team directly.

People are potentially impacted by Space use in many ways, including:

Limited or lack of available Space – when someone wants to use a specific Space or type of Space, there is none available. For example, someone wants a four-person meeting room but no meeting rooms are available that can accommodate four people, or someone wants to use a workstation but all workstations are Apparently Occupied.

Shortages or queuing for services – high Physical Utilization can lead to strain on the facility services that can adversely impact those using the facility. For example, there may be waits for beverages or toilet facilities, or certain consumables may run out.

Impaired working environment – high Physical Utilization near or above the design intent may also impact someone’s ability to feel comfortable working. This might be due to excess noise or distraction, or insufficient privacy or space.

Absence of social interaction and serendipity – low Physical Utilization can lead to lower levels of interaction and collaboration. This can impact both innovation (often fuelled by serendipitous interactions) and wellbeing (due to lower levels of social interaction and increased isolation in the workplace).

Availability

The first of these impacts – limited or lack of available Space – is related to Utilization but Utilization alone cannot answer all questions of availability. This is because Utilization describes the use of Space, but it does not consider the demand for Space. Let us define some terms that will help discuss these topics:

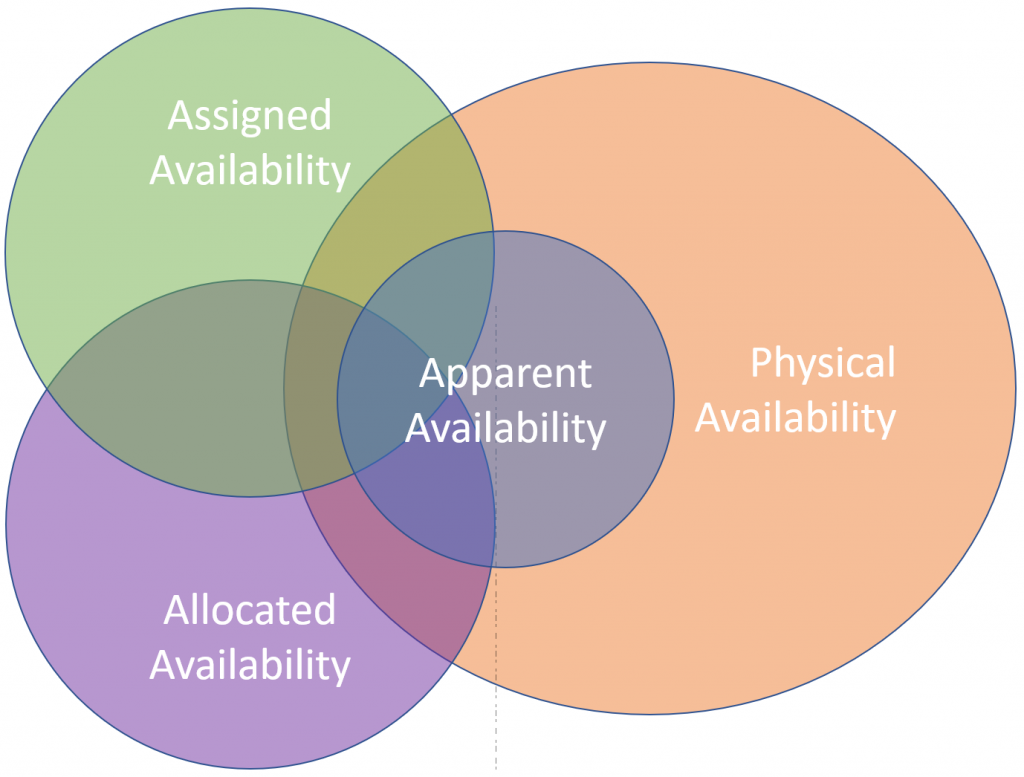

Availability is the opposite of Occupancy. In simple terms a Space is either Occupied or it is Available. Similarly to Occupancy, Availability may be Physical, Apparent, Assigned (more usually called Vacant), or Allocated.

PHYSICAL AVAILABILITY

No physical presence in the Space, for example a desk without a person (even if there is Trace Occupancy), or a car parking space with no car in it.

Unlike Occupancy, Availability does not define “Trace Availability”. This is because the concept of “Trace Occupancy” exists to identify Spaces that are not physically occupied but are clearly in (recent or impending) use based on there being ‘traces’ of occupancy (jackets, laptops, notebooks, coffee mugs etc.). It does not make sense to define “traces of availability”, since this would suggest some indication that the Space is not in use. The only such indication is that there are no traces of occupancy. Therefore, when discussing Availability, Apparent Availability is used:

APPARENT AVAILABILITY

The appearance that a space is unoccupied, by both no Physical Occupancy and no Trace Occupancy.

ASSIGNED AVAILABILITY/ VACANCY [1]

Space that is not assigned to a specific individual or group of individuals.

The assignment may be indefinite or for a fixed period, and Assigned Availability does not depend on the Physical Availability or Apparent Availability of the Space, but only on the systematic absence of an assignment of specific people to the Space.

Assigned Availability is also known as Vacancy.

ALLOCATED AVAILABILITY

Space that is not Allocated to any organizational unit, or that is allocated to a ‘dummy’ organizational unit to reflect the absence of an allocation, for example the allocation of vacant space to the corporate real estate organizational unit, or allocations to ‘reserve’ organizational units that mirror reserve accounts or provisions.

To help explain how these types of availability interact, the Venn diagram below shows how Space can belong to multiple availability types:

NOTE: Although the diagram above suggests that Space can have Allocated Availability without Assigned Availability, this combination is highly unusual, as it indicates the Space is assigned to specific people but not to any organizational unit. As discussed in the earlier section on Occupancy, this situation occurs when there is a secondary re-allocation of the Space even though it isn’t directly allocated to an organizational unit. Another example is where a Space is entirely vacant – without and furniture, fittings or equipment (for example prepared for subletting) – and not allocated to an organizational unit. Such a Space has Allocated Availability, but no Assigned Availability (because there are no resources to assign).

Demand and Constraints

Availability is so important because it acts as a constraint on the choices open to someone when they are deciding on a work setting for an Activity. The ability for Space users to be able to choose an appropriate work setting for their activity is at the heart of many contemporary office design methodologies, and therefore any constraints on users’ freedom of choice are potentially very significant.

To express this process of choosing, we must define the concept of Space Demand:

SPACE DEMAND

The aggregate desire to occupy a Space in the absence of constraints.

Space Demand therefore expresses what the users would choose if they had a free, unconstrained choice that was not limited by Availability or the actions of other users.

However, the workplace is not unconstrained, and therefore we must consider:

DEMAND SATISFACTION

Measures the extent to which Space Demand is satisfied at a point in time (a Snapshot) or over a Period, as a ratio of the satisfied Space Demand to the total Space Demand

Demand Satisfaction is the primary objective of an organization’s facilities manager, who is tasked with providing Space in which the organization’s activities can take place – i.e. ensuring high (or very high) Demand Satisfaction. Achieving this with a high level of Utilization is a secondary objective.

In practice, it is likely that many choices will be constrained. For example, selection of a conference room will likely be constrained by other existing reservations.

Constraints may arise from several sources, and Availability of the Space is just one. For example, when scheduling a meeting, the availability of the other people attending the meeting will also be a constraint, as may their working hours and time zone.

Due to such constraints, Space Demand may be satisfied, unsatisfied, or partially satisfied:

SATISFIED DEMAND

The Space Demand was satisfied because the desired Space (or an alternative Space that is identical to the desired Space in all significant ways) is available for the chosen Period.

Partially Satisfied Demand occurs when an Activity is displaced. Some activities have precise space demands. but for many there could be a suitable alternative Space. It is possible for an Activity to be displaced in time as well as Space (i.e. by performing the Activity at a different time, either in the original desired Space or an alternative). However, activities that are displaced in time are considered as Unsatisfied Demand from our perspective of occupancy analytics.

Displacement must be carefully considered when analyzing Demand Satisfaction, because it can mask the real impact of certain policies. For example, in the world of crime prevention, one may think that installing window locks on homes would reduce crime. However, crime prevention experts suggest that a criminal will perform a crime if three conditions are met: (i) they are motivated to do so (have desire), (ii) belief that they can get away with the crime; and (iii) an opportunity to perform the crime. A window lock has no effect on (i), and is most likely to simply lead the criminal to find another house without locks – in other words to displace the crime – rather than reduce the crime.

Similarly, workplace policies designed to address some undesirable behaviour, may unintentionally lead to displacement rather than real reduction. For example, in a large corporation a reservation system was introduced that required check-in at the start of a meeting to confirm that the meeting was taking place. The intent was to reduce the number of meeting rooms that were booked but not used by gathering data on the main culprits in making these reservations and helping them understand the importance of avoiding this behaviour. However, in response to this, the main culprits – who tended to be senior managers with personal assistants – simply had their personal assistants going to each room they had reserved and checking-in, irrespective of whether or not the meeting was actually going to take place. This undermined the occupancy analytics and fed a culture of “undermining the system”, rather than the raised awareness and cooperative spirit that had been hoped for.

Partially Satisfied Demand and Unsatisfied Demand are interesting when analysing Occupancy because they provide insights into the degree of compromise that users are making in their Space selection, particularly in activity-based working styles.

They also provide insight not possible from Utilization alone. For example a Space that is 100% Utilized but with no Unsatisfied Demand could be considered maximally efficient; however, a Space with 100% utilization and significant Unsatisfied Demand is likely to be having a significant adverse effect on the people using the Space (possibly in reduced productivity, lower employee engagement, or reduced well-being).

Demand Satisfaction can be measured in two different ways:

THRESHOLD DEMAND SATISFACTION

If the Space Demand is satisfied at a point in time, the snapshot value of the Threshold Demand Satisfaction is 100%; otherwise the snapshot value is 0%. Over a Period, the Threshold Demand Satisfaction is the proportion of the Period for which the snapshot value is 100%.

Threshold Demand Satisfaction always describes the proportion of time that Space Demand is satisfied. However, it does not indicate the extent to which Space Demand was unsatisfied during the Period, nor can it be calculated using the three measures of Space; Area, Capacity/Census and Resource Count. To allow for these factors to be analysed, we define:

SCALED DEMAND SATISFACTION

The proportion of the Space Demand that is satisfied. If all Space Demand is satisfied, the Scaled Demand Satisfaction is 100%. If only some of the Space Demand is satisfied, then the Scaled Demand Satisfaction is the proportion of the Space Demand that is satisfied compared to the total Space Demand. This can be calculated at a Snapshot or over a Period, and may be calculated using the same units as Space – Area, Capacity/Census or Resource Count.

Demand Satisfaction cannot normally be determined by observation, as it relies on a measurement for total Space Demand which includes the Unsatisfied Demand – but Unsatisfied Demand does not take place in the Space and therefore cannot be observed. In some circumstances, Unsatisfied Demand might be indicated by queueing as a queue contains people whose Space Demand could not be satisfied at the time they desired. However, even in these circumstances, it is difficult to accurately measure the total demand.

FOOTNOTES:

- It is often useful to distinguish Vacancy within an otherwise Occupied area from Vacancy that is self-contained. Self-contained Vacancy is likely to be a candidate for reduction or subletting; Vacancy within an Occupied area may be structural or may indicate an opportunity for a re-stack (this Space is sometimes referred to as Unoccupied to distinguish from other Vacant space).