Really Big Inc. was doing well. Turnover was up for the fifth year in a row and at a record high in their one hundred year history. Profits had dipped a bit but were still ok. According to most analysts, they had weathered the market uncertainty.

But there was a pinch.

Really Big Inc. faced a new kind of challenge from several smaller, more agile businesses.

These competitors had brought innovations from other sectors – particularly the use of online-only channels – and managed to secure a small but significant market share in just a few years.

Jake knew it was time to respond. As CFO, he could see very clearly how the historical gross margins that Really Big Inc. had been able to achieve could no longer be sustained without something shifting.

He had sat through many meetings already listening to how Really Big Inc. was going to differentiate itself; how it was going to improve customer service, increase customer satisfaction, create more brand loyalty. And Jake had some really smart colleagues whom he had faith in. But if they were going to stop the net margins sliding, he had to focus on the cost base.

As he sat in his corner office looking out over the Manhattan skyline from the 45th floor of Really Big Inc’s headquarters, he had an idea. This building was nice – really nice – and had been the company’s HQ for more than 80 years. Nearly 2,000 staff worked there. With the prestige of this amazing Manhattan landmark came Manhattan salaries and benefits. Jake wondered: how many of these people really needed to be right here?

By the end of the following week, the task force Jake had assembled had already come up with the outline of a plan to establish how many of these roles really needed to be in the HQ, and how many could be relocated to other Really Big Inc offices in Texas or California that showed a considerably lower cost of employment. They had in-principle support from the board and an embryonic communications plan – everyone agreed the comms would have to be great as this would not be the most popular program for sure.

By the end of the following quarter the plans were laid, and Jake himself called an all-hands meeting to make the announcement: over the next six months they would be reviewing all roles based in Manhattan and identifying those that could just as well be conducted from Lancaster CA, Fort Worth TX, or (a late addition) Meridian MS. He explained this would be followed by a twelve month transition program for those roles impacted, with generous relocation allowances. Importantly no one would be made redundant.

The staff were worried. The board was optimistic. Down in facilities, Matt – the Head of Workplace – wasn’t quite sure the cafeteria was going to cope with everyone being in the office for an all-hands meeting.

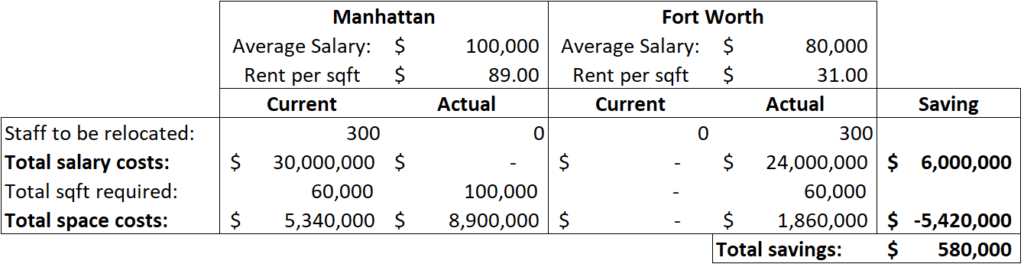

Matt also began to wonder how this change was going to impact his flagship building. He had heard on the grapevine – since Jake hadn’t invited Matt onto the task force – that the company expected 25% of the roles to be relocated. Five hundred people. That was several floors’ worth of space. Matt had already had a conversation with Jake about the likely impact and Jake had said that was a big part of the point: the people were most expensive but second on his cost-base was real estate, so freeing up the space for sublet made a really significant contribution to the viability of the program. Jake had told Matt to sit tight for now though until they knew the number of roles moving.

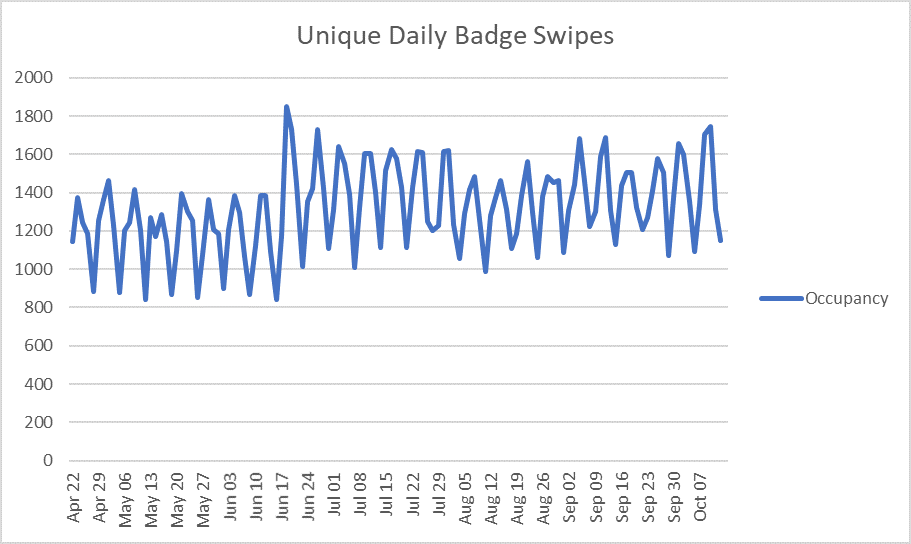

A few months passed, and one morning Matt was reviewing his monthly management information pack over a strong black coffee in the cafeteria when his eye was drawn to the Occupancy trend – could that be right? He set off in search of Nina, his occupancy analyst.

Nina explained that she also thought the figures were surprising, but had double checked everything and they were right: the most recent quarter had seen increased occupancy of nearly 20%. Nina said she had checked with HR and there hadn’t been any significant headcount increase, in fact the opposite – there had been a little attrition since the announcement and HR were recruiting. The conference centre reported that there weren’t any unusual events recently.

Matt and Nina looked carefully at the data for the last year to see when this had started. They found it – an occupancy spike followed by a sustained 20% (give-or-take) step-up in the occupancy. Matt reached for his phone and started scrolling back to find that date in his calendar.

It was Jake’s all-hands meeting.

It began to dawn on Matt and Nina what was going on: on that day, almost everyone had been brought in to the office to be told, essentially, “if you don’t need to be in this office, you’re going to find yourself moving to California, Texas or Mississippi”.

It is no surprise that the very next day people who normally worked from home or spent most of their week out with customers or suppliers choose to spend more time in the office. After all, if they could work from home they could work from California.

Matt realized that the on-going communications about the program that were intended to make people feel included and try to allay their worst fears were serving to sustain this behaviour. The perceived need for presenteeism over several months had now led to many people simply seeing this as “the new normal”, with their habits, rituals and home life now fully adapted to being in the office more.

This uplift in Physical Occupancy was putting a strain on the facility, and Matt had already noticed a corresponding increase in service requests, energy consumption and demand for consumables.

Matt and Nina followed the occupancy analysis over the next twelve months, sharing what they saw with Jake. In the end, much to Jake’s disappointment, the program only yielded 15% of the roles as “relocatable”, and many of the people in those roles chose to stay in NYC rather than move, losing a lot of experience and knowledge from the company.

But worse still from Jake’s perspective was the fact that the increased occupancy persisted throughout, and the net result was that even after the roles had been moved, the building occupancy was slightly higher than before. That meant no savings on the Manhattan real estate costs but still the need to take on an extra 35,000sqft in Fort Worth (where most of the roles ended up being relocated to).

When Jake did the final analysis, he realized that the program had been a poor choice: there were lots of one-time costs in running the program, funding relocation packages, recruiting to fill vacancies left by those who didn’t decide to move, and yet after everything, the total operating costs had barely changed.

In the program review, Matt, Nina and Jake felt that an important lesson had been learned: that people’s demand for space can be significantly varied – often in unintended ways – through communication.